Why Healthcare Costs Are So High, Providers Ditching Their Health Plana, Amazon AI, and More

In this update we review what the data tells us on why healthcare is so expensive in the U.S. We see that causes are many, and no single cause explains the high cost. We review the latest regulatory pressures on PBMs and insurer prior authorizations recognizing pressures will continue. Turing out attention to health systems, we explore the trend in providers exiting their health insurance ventures. Finally, we review Amazon's new AI technology, Nova Act, and other developments in AI drawing insights for leaders.

Joe Bastante

5/13/20259 min read

In this month’s update:

Why healthcare costs so much and what the data tell us

PBMs and prior authorizations, are regulators going to stop hating on them?

Why many health systems are ditching their health plans

Amazon's new AI, what it is and lessons leaders should take away

Why the Model Context Protocol (MCP) is important, even for business leaders

Why healthcare costs so much and what the data tell us

Explaining why U.S. healthcare is so expensive might be more than we can cover in a brief summary, but let's see how deep we can go. To begin with, U.S. healthcare spend has been accelerating. The average annual growth rate was 4.1% in the 2010's, then 4.6% 2021-2022, then 7.5% 2022-2023. PwC is estimating 7.5-8% growth in 2025.

Pharmaceutical Companies: Many blame "drug companies" for the rising costs. In fact, from 2020-2023, retail drug spend grew 8.6% per year, more than 2% faster than hospital and physician spend. However, net prices (after discounts and rebates) have actually been growing slower than inflation even decreasing in recent years, with continued decreases projected in the coming years (-1 to -4% decrease per year is expected). Increased drug spend is driven by a relatively small proportion of medicines (e.g., GLP-1s with global revenue of ~$50bn in 2024). Generic and biosimilar medications lessen costs accounting for more than 90% of all prescriptions but only 18% of prescription spending. Of course, the U.S. carries a disproportionate burden of drug costs paying 2.78 times the cost of other developed countries and 4.22 times the cost for generic drugs, so higher costs are included in our current cost structure. President Trump is seeking a mandate this month to have lower "most favored nation drug pricing" for low-income and disabled citizens.

Hospitals: Some blame high costs on hospitals given recent cost growth of about 6.2% annually. Some blame hospital consolidations, which lead to price increases of 6 to 17 percent (some say it's greater than 50%, which seems high). While hospital margins improved overall (to 6% on average per Strata's 1,600 hospital database), total expenses were up 5.4%. Furthermore, 60% of hospital costs are labor related, and labor cost growth has been exceeding inflation. So, costs are rising, but so are expenses.

Insurance Companies and Brokers: Some blame insurance companies for rising costs. In fact, most lines of business have restrictions on the percentage of premiums that can be kept by insurers to operate their plans and draw a profit. Furthermore, recent years have been difficult for most insurers. For example, Blue Cross companies on average had an operating loss of 2.9% in 2024. Of course, some years have been better, and insurers benefit from rising costs as their cut grows in proportion to rising costs overall.

Some blame insurance brokers. The Senate Finance Committee reported that MA broker commissions rose to $6.9 billion in 2023 from $2.4 billion in 2018. However, in 2024, Elevance, Cigna, Aetna, Centene, and others eliminated paying broker commissions for some of their products.

The Government and All of Us: Perhaps we can blame the government, whose stream of payer and provider mandates have cost healthcare companies billions. Or we can blame people and society. A Brown & Brown analysis found that high-cost claimants (the number of claimants per 1,000 incurring $250,000 or more of spend), grew by over 50% from 2021 to 2024. This growth was driven by a significant increase in the number of ill members, not higher costs per member. Earlier we noted excessive GLP-1 costs, but spend is driven not by price alone but by high rates of obesity and avoidable type-2 diabetes. So, what shall we conclude? There may be some hot spots but there's no smoking gun. We healthcare leaders need to avoid blaming others and do the difficult work of reducing the costs we can influence. Perhaps the single best thing all of us can do is keep ourselves and our families as healthy as possible.

IQVIA report on healthcare usage and spend:

KFF Health System spending trend data and projections:

Data on high-cost claimants

https://www.bbrown.com/us/insight/2025-healthcare-cost-outlook-drivers-trend-insights/

Research on U.S. drug prices compared to other countries:

PBMs and prior authorizations, are regulators going to stop hating on them?

The short answer is no. Since we've covered both PBMs and prior auths recently, let's review recent updates. For PBMs, they bear the perception of gaming the system to maximally extract profit. Recall last month's story where employees brought a lawsuit against JPMorgan, their employer, effectively claiming they were complicit in allowing CVS to overcharge for medications. If you'd like a sense of how the Federal Trade Commission feels about PMBs, check the link below (they have a dedicated page). The FTC filed a lawsuit in April against large PBMs accusing them of inflating insulin prices through anticompetitive behaviors. At that site you'll find FTC reports claiming, for example, that the large PBMs "imposed markups of hundreds and thousands of percent on numerous specialty generic drugs dispensed at their affiliated pharmacies—including drugs used to treat cancer, HIV, and other serious diseases and conditions." States continue to get involved. For example, in Arkansas, a law was signed in April banning PBMs from owning pharmacies. You can find a link below to PBM-related legislation at the state level.

For prior auths, Bloomberg reported this past week that the CMS is considering a proposal to scale back prior authorizations. While the CMS has already passed prior authorization rules, e.g., within the CMS Interoperability and Prior Authorization Final Rule, many states are taking it further with their own legislation. For a recent example, California has a package of bills making their way through approvals. If approved, it would constrain prior auths by requiring insurers' prior auth determinations to be made by a physician with the corresponding specialty and would eliminate prior auths that are historically approved 90% of the time or more. I can't help but notice that the 90% approval rule could have unintended consequences in encouraging fewer approvals. California isn't alone in their legislation; many states have such laws some fairly extensive (see the link below). For example, Minnesota disallows non-medication prior auths for cancer and behavioral health treatment.

Whatever the ultimate rules, it would be far better if a uniform rule were implemented at the federal level. These state-by-state laws add complexity making healthcare costly and confusing. Check out two useful links below, one on the 10 states recently going after prior auths and the other an American Medical Association tracker for state-level prior auth legislation.

FTC site listing PBM legal actions and reports::

A well-laid out list of pharmacy-related laws by state:

https://nashp.org/state-tracker/state-drug-pricing-laws-2017-2025/

Report on 10 states tackling prior auths in 2024:

AMA' s list of prior auth requirements by state:

https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/prior-authorization-state-law-chart.pdf

Why many health systems are ditching their health plans

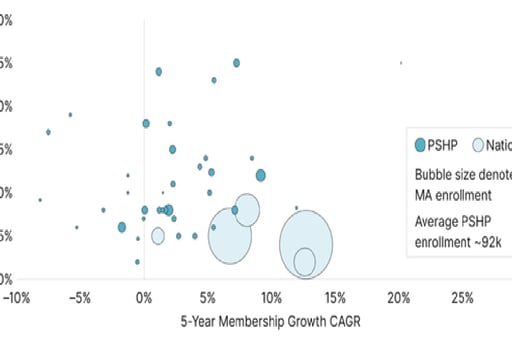

A considerable number of providers who had launched insurance plans have eliminated them or scaled back. I almost wrote about this topic a few months back, but I wasn't yet certain it was a clear trend. I had worked for an organization who had a joint insurance venture with a large health system. Ultimately, the health system exited. This has become a common scenario. For example, N.C.-based Novant Health sold its stake in the HealthTeam Advantage plan, Ill.-based Carle Health will wind down its individual and employer group plan (Health Alliance) and also wind down a joint venture with FirstCarolinaCare, Minn.-based HealthPartners is scaling back its plans, and Indianapolis-based Indiana University Health sold its plan to Elevance. These are just a few examples of exits or reductions in insurance offerings by providers. Why are they exiting? Reasons are many, high care utilization and costs, significant financial risk, extensive and increasing regulations including growth in state-specific regulations, burdensome reporting requirements, changes in risk adjustment rules reducing reimbursement, increasing audits, and more. It's quite difficult for small provider-owned plans to provide for these demands without incurring financial loss. Consider the graph below from Guidehouse in 2024 comparing provider-sponsored health plans to national insurers. Notice how smaller provider-sponsored plans generally have medical loss ratios high enough where profit and even sustainability are difficult. While some providers have been successful, like Kaiser Permanente and UPMC Health, most providers without scale should generally avoid building health plans unless they are prepared for the inevitable cost, difficulties, ongoing investment requirements, and headwinds. Mergers and acquisitions may be a more feasible alternative, though the strategic implications are significant warranting careful consideration.

The Guidehouse article referenced above:

https://guidehouse.com/insights/healthcare/2024/medicare-advantage-sustainability

Amazon's new AI, what it is and lessons leaders should take away

I recently tried Amazon's Nova Act, a new "agentic" offering for operating a user's screen using AI. Most frontier LLM vendors now have such a tool. So how does it work? It's used from Python code to create modular and reusable agents. While there is a bit of coding, instructions are passed to Nova Act in simple language, for example, "Go to Yahoo Finance, read the first four headlines and tell me if today's mood is bearish or bullish." Overall, I like the design allowing stringing together of pre-created scripts. I tested a use case instructing Nova Act to go to Amazon, search for classical guitar strings and create a data structure with descriptions and prices for 5-star rated strings. Did it work? Somewhat. First, it was very slow, way slower than a human. It also struggled with paging down through results. For example, the Amazon screen showed pictures of guitar strings with part of the description showing and part cut off requiring scrolling down. These tools work by taking a picture of the screen, analyzing it, paging down, taking another picture of the screen and analyzing again. But a single description spanned two screenshots, which confused it. It's not that it can't be made to work, but it's a hassle and way to slow.

I've talked to many who think these tools are quantum leaps and groundbreaking but consider this. Nova Act uses software called Playwright, which isn't new. Playwright is the tool that's controlling the user's browser. It's often used for automating system testing. Nova Act figures out how to instruct Playwright to interact with the screen rather than a programmer directly telling Playwright what to do. Therefore, Nova Act is adding intelligence, but it's built on the foundation of past innovations. So here are the key takeaways for leaders. First, these AI tools will be highly useful ultimately acting in the place of humans, but they have a way to go to be broadly useful. More importantly, what may seem like out-of-the-blue and disruptive technology is really the incremental adding of new to old. I dislike the term "agentic" since it hides the reality of incremental technology progress and suggests an instant intelligence revolution. This is not true. Organizations need to advance daily with technology continuously learning, exploring, and adopting. This is an ongoing discipline to be mastered and bears more fruit than merely chasing AI. If it's not absolutely clear who in your organization owns this discipline, then that's the most important call to action.

Amazon post introducing Nova Act:

GitHub repository for any who would like to try or have their teams try it:

https://github.com/aws/nova-act

Why the Model Context Protocol (MCP) is important, even for business leaders

Having just covered Amazon Nova Act, it may seem I'm suggesting LLMs have a way to go before they can take useful actions on behalf of users. This is true for Nova Act because it's visually trying to understand screens and systems, which were designed for humans not computers. However, LLMs can integrate programmatically not relying on screens. This is possible and enabled through the new Model Context Protocol (MCP). MCP is a standard way of giving LLMs access to data, tools, and services without going through user interfaces. For example, a practice management system vendor could use MCP to implement a service that LLMs can use to search for and book appointments. A user can then ask, "are there any appointments this week before 10:00 am and if so, can you book an appointment for me." The LLM will know what to do. Commercial software vendors will continue to add MCP support allowing LLMs to interact with their services. For example, PayPal provides support for MCP allowing LLMs to make payments on a user's behalf. The key takeaway for leaders is that technology is now available allowing AI/LLMs to use and interact with your systems , data, and commercial services. This will evolve quickly; it's definitely a topic I'll track. It's important to understand that LLMs are not able to be tested in the same way or to the same extent as traditional code. Therefore, I'd not yet conduct critical transactions this way. Yet, it opens a whole new world in which LLMs can escape their chat windows and interact with technology on our behalf.

If you'd like a simple summary of MCP and watch a few use cases in action, check out Anthropic's page:

As always, feedback, suggested topics, or questions are welcomed. I’m here to help. Contact me anytime.

Contact us

Whether you have a request, a query, or want to work with us, use the form below to get in touch with our team.